Distribution

Ticks are found throughout WA in bushland or long, grassy environments where they may climb up blades of grass or vegetation and wait for a host (animal or person) to pass by. They can also actively move toward a host, so care should be taken when resting in open natural environments, including nature reserves, designated clearings and camp grounds.

Activity

Peak tick season in WA runs from September to April. This coincides with the spring, summer and autumn months, when the weather is warmer.

Life cycle

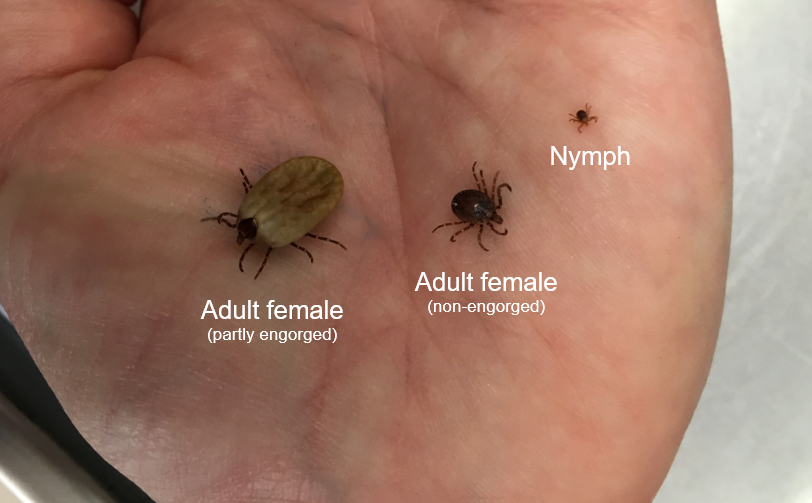

A tick life cycle generally involves four stages: egg, larva, nymph and adult. It can take up to three years for a tick to complete its life cycle, but many die in process, seeking a host.

Ornate kangaroo tick (Amblyomma triguttatum)

All female ticks need to take a blood meal before producing eggs. Once engorged, the female will drop from the host and lay a clutch of eggs. Larval ticks hatch and can survive for weeks without a bloodmeal. Larvae will then attach to a host and feed over several days, before dropping off to moult to the nymph stage. The cycle is then repeated, with the adult tick reaching maturation on its third host.

Larvae and nymphs require a blood meal to grow and moult from one stage to the next. Adult female ticks require a blood meal to produce eggs. Adult males feed very little on blood and tend to seek a host in order to find a female tick. Ticks range in size from smaller than a pin head (larva) to as large as a marble (engorged adult). Their colours also vary from shades of brown and reddish brown, to grey and black. Ticks can even appear a bluish-grey if they have taken a large blood meal.

During the feeding process, ticks cut the surface of the skin with their mouthparts, insert a feeding tube and secrete saliva containing anaesthetic properties so the host cannot feel the tick has attached itself. Unlike mosquitoes which feed for a matter of seconds, hard ticks can remain attached for several days. Once embedded in the skin, tick saliva creates a pool of lysed tissue and capillaries below the skin surface, allowing a constant supply of liquid nutrients.

Most ticks will feed on a new host at each stage of their life cycle. While ticks parasitise a range of animals including mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians, many tick species have a host preference.